Mevers' research group isolates bacterial symbionts associated with tropical marine egg masses, investigates the chemical potential of the symbionts using various analytical techniques, and leverages the identified metabolites for biomedical potential.

New treatments for infection, also known as antibiotics and antivirals, are needed desperately as new pathogens continuously emerge and current treatments lose efficacy.

Emily Mevers, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry, part of the Virginia Tech College of Science, recently received a five-year, $1.9 million grant from the National Institutes of Health that aims to leverage the microbiomes of marine egg masses for the development of next-generation antibiotics to treat emerging pathogens.

The specific grant is an Early-Stage Investigator Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award, which provides young investigators with the flexibility to pursue a breakthrough discovery by following up on unexpected findings that were not in the original research proposal.

Natural products are small molecules that offer an advantage for the producing organism. Natural products are special molecules, as they have evolved in nature to serve a specific function for the producing organism. Many of these functions have the potential for the treatment of disease in humans.

For example, most of the antibiotics we use in clinics are produced by microbes to outcompete competitors in the environment. Nearly 60 percent of all small molecule therapeutics approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are related to a natural product.

“Natural products have historically played a critical role in drug discovery,” said Mevers. “However, it is getting harder to find new molecules, so we need to get more creative in the places we search for these molecules.”

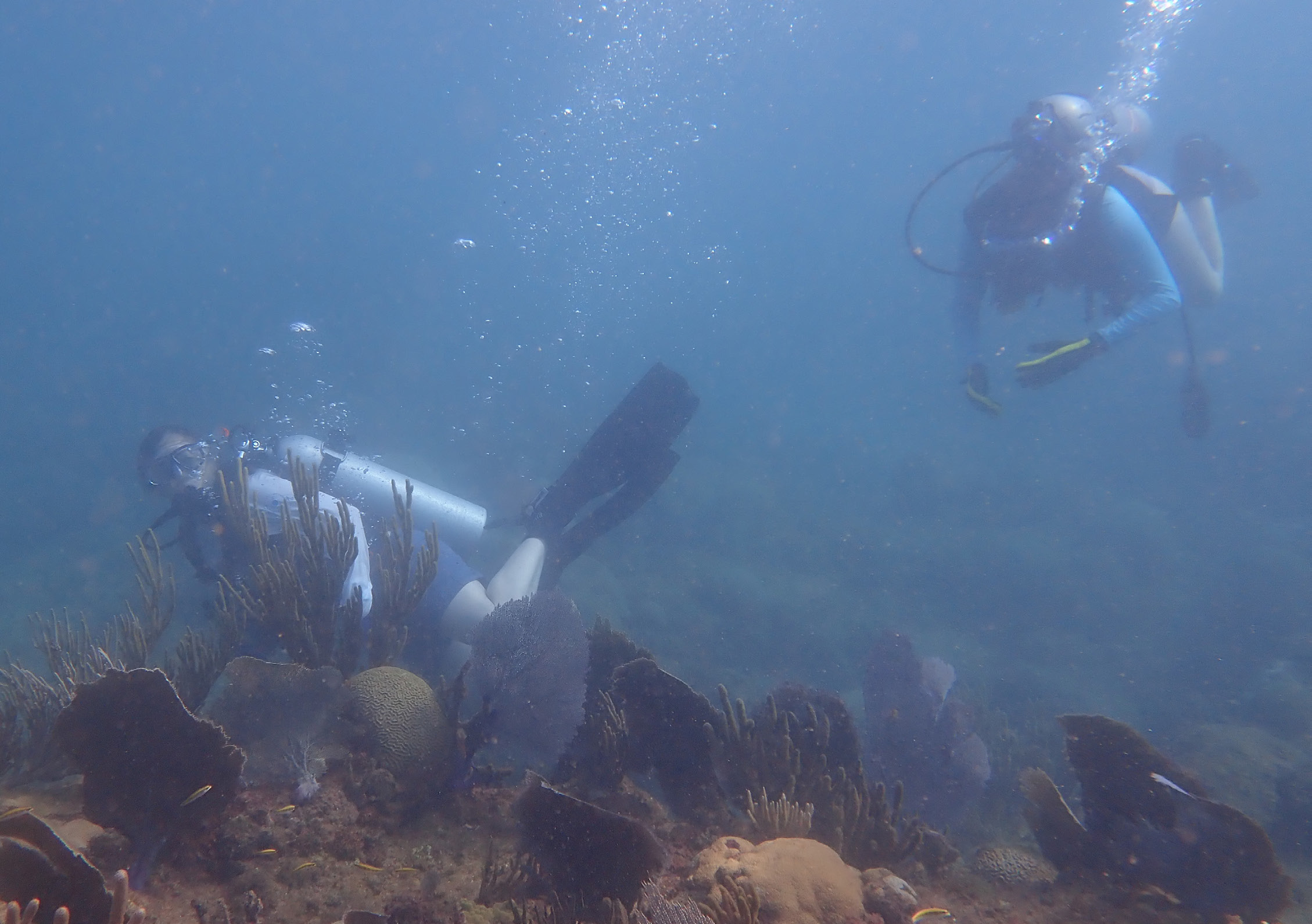

The Mevers lab uses an ecology-driven approach to identify environmental niches that are likely to have led to the evolution of unique antibiotics. Researchers' current focus is the microbiome of marine egg masses from southwest Florida and Puerto Rico, as many egg masses have no physical defense mechanism from predators. First, the lab identifies diverse bacterial symbionts, microorganisms that live associated with the egg masses, and then assembles a library of the natural products produced by these symbionts that will be screened for antibiotic activity.

The goal is to leverage the ability of isolated microbes to produce new metabolites, because less than a fourth of the natural products are produced under typical laboratory conditions.

“Bacteria in the environment have to fight for food and space, but when we grow them in the laboratory, we provide the bacteria with a plethora of food and space, so it has no need to produce antibiotics,” said Mevers, an affiliated faculty member of the Virginia Tech Center for Drug Discovery.

“My group is quite interested in developing new methods that replicate environmental conditions in the laboratory, such as growing the bacteria in complex communities similar to those found within individual egg masses. This will allow us to replicate many of the important interactions that occur in the environment, which are known to play an important role in regulating these silent metabolites.”

The recent Hurricane Fiona had a terrible impact on Puerto Rico, one of Mevers’ two main collection sites. “Our collection sites are in the southwest region of Puerto Rico, and from what I can tell from news reports, that area was hit very hard by the hurricane and subsequent flooding,” Mevers said. “Most buildings have significant water damage from the multiple feet of water that flooded the city. … It will take a while to know the entire impact this hurricane will have on our research activities.”

Ultimately, the Mevers group hopes to use this grant to identify novel natural products with pharmaceutical potential in order to repopulate the drug pipeline for the treatment of infectious diseases.

“The need for new anti-infectives and agents modulating the immune system is more evident today than ever before as novel pathogens continuously emerge and old treatments lose efficacy,” Mevers said.

Page 1 of 6 | 18 Results